ЕкоEconomic development, greater regional stability, avoiding local conflicts but also decreasing the risk of the Balkans to become “hot” frontal line of the clash of the West with Russia – these are the main benefits of the resolution of the long-standing Greek-Macedonian dispute, said four Balkan analysts in their analyses on the Prespa Agreement.

The policy papers are authored by professor Dimitar Bechev, analyst Igor Bandovic and the professors Nenad Markovic and Ivan Damjanovski. The authors analyze the Prespa Agreement in terms of the current geopolitical state, both in the Balkans and globally, entering the constellation of intra-political relations in Macedonia and pointing out to the possible scenarios if Athens and Skopje succeed or fail to implement what’s been agreed.

The analyses were written prior to the referendum in Macedonia.

European perspective

Enlargement used to be the EU’s trademark policy, but that is not the case anymore, according to the Bulgarian professor Bechev.

“French President Emmanuel Macron, amongst others, seems to believe widening runs counter to deepening. Democratic backsliding in Hungary and Poland is hardly a reassuring precedent, let alone the chronic deficit of rule of law in Romania and Bulgaria” he says in his analysis “The Macedonian Name Agreement and Its Aftermath: A Geopolitical Perspective”.

Professor Dimitar Bechev,

one of the authors of the analysis

He deems the conditional offer for starting accession talks, given in June 2018, “a halfway decision typical of the EU”.

Therefore, Bechev believes that the success from Prespa will be a success for Brussels, in terms of injecting fresh air in this vital process of preserving peace and stability on the European continent.

His views are shared by the Serbian international relations expert, Bandovic, who believes that the Agreement is one of the most important outcomes of the regional cooperation between the Western Balkan states, which was intensified and gained prominence after the German government launched the Berlin Process in 2014.

“One of the significant achievement in Vienna in 2015 was the signing of the Declaration on resolving bilateral issues by the foreign ministers of the Western Balkan countries in which they ‘commit themselves to a resolution of all open bilateral questions in the spirit of good neighbourly relations and shared commitment to EU integration’. The political push towards resolving these issues from the EU side created a favourable momentum in the region”, Bandovic says.

He points out that first great success of this process would be the resolution of one of the two biggest bilateral disputes, between Greece and Macedonia, like an impulse for a significant shift in the second – between Serbia and Kosovo.

In this regard, Markovic and Damjanovski link the resolution of this dispute directly with Union’s and NATO’s need to preserve peace within their borders, but also to prevent stratification of countries, reminding that the Agreement was welcomed by many EU and NATO member-states, while the supporters of the Prespa document oftentimes emphasize Greece’s “gate keeping role” in both organizations in their narrative.

NATO as peace guarantee

Markovic and Damjanovski pay special attention to the effects of the possible (non-)joining of NATO, as a more feasible objective. On the one hand, a positive outcome can bring long-term stability, while on the other, the negative one, may “shake up” the Balkans once again.

Prime Ministers Zoran Zaev and Alexis Tsipras at the signing of the Prespa Agreement

“As soon as Macedonia’s western partners stepped up into finding a political solution, they regained their previous popularity. Additionally, the constant presence of Turkey and its popularity among the Muslim population in the country, followed by visible financial incentives, should also be taken in consideration as a variable in terms of political stability and security of the country, given the growing gap between Erdogan’s regime and EU and NATO interests” the professors of Skopje’s Iustinianus Primus say.

They have no doubt that in case of negative outcome in this process, the NATO and EU leverage risks decreasing once again because of widespread disappointment and the missed opportunity. Especially when it comes to the fact that it would be the second event of such kind in just 10 years (after the Bucharest veto), therefore “it is safe to assume that the decrease in confidence for NATO accession will occur faster than previously offering less space for damage control”.

With regard to this, Bechev’s stance is quite interesting, who puts the success of the Prespa process in even wider context.

He believes that although US President Donald Trump may be giving European allies a hard time, still “NATO is in fairly good shape”.

Following the annexation of Crimea in March 2014, he says, the Alliance rediscovered its core mission of defending its members against external threats, as enshrined in Article V of the Atlantic Treaty. Enlargement is proceeding at a steady pace, too. Montenegro joined in June 2017 and Macedonia obtained an invitation at the summit in Brussels (July 2018). However, behind all of this stands one big “BUT”, which is related to the final outcome of the name dispute.

“For Macedonia, membership means security. Each of the main communities stands to benefit. Macedonians would be reassured about the future of the state while Albanians, amongst whom support for NATO and the US is traditionally high, will see expanded links with the West as an instrument to cement political gains they have made over the past two decades. Macedonia’s entry into the Atlantic Alliance won’t necessarily bridge the ethnic divide, yet it might dissuade political entrepreneurs from exploiting it and thus create a higher degree of unity” Bechev says.

Which are Russia’s interests in the story

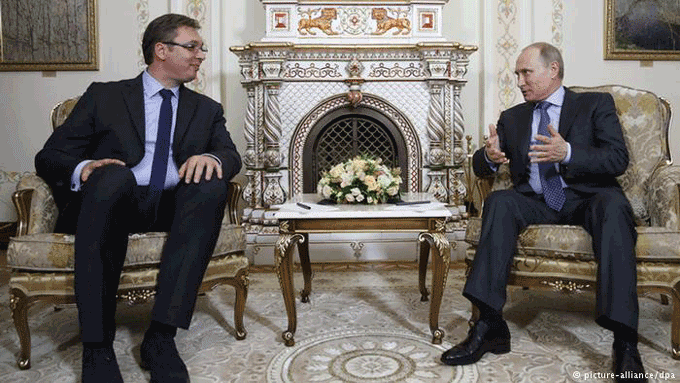

The three analyses contain the stance that the Balkan equation cannot be written properly without calculating Moscow’s interest. Direct influence of the Russian Federation in Macedonia, but also the immediate one, through the pro-Russian authorities in neighboring Serbia, are subject of the analyses too.

Vučić praised Gruevski and his government standing up against external influences, Bandovic says

Bandovic pays a fair amount of attention to Macedonia’s relations with Serbia, which have become rather tense.

“The former Macedonian leadership enjoyed strong support from the then Prime Minister Aleksandar Vučić and his political party. When the wire-tapping scandal developed into a full-fledged political crisis, with daily protests, an orchestrated campaign against change of government in Skopje was launched in pro-government tabloids in Serbia. Accusations that the new government will enable the creation of a ‘Greater Albania’, and play into the hands of the Albanians that are in favour of the dissolution of Macedonia became common currency in pro-Vučić press. Serbia was highly involved in the political crisis and Vučić praised Gruevski and his government standing up against external influences and foreign mercenaries and agents”, Bandovic says.

He reminds of the bloody 27 April 2017 events and the scandal with Goran Živaljević, a Serbian intelligence officer from Serbia’s embassy in Skopje who was amongst the mob that stormed the Parliament building.

He also points out to the research carried out by investigative portal KRIK and OCCRP which published transcripts of conversations between Živaljević, a pro-Russian Macedonian politician and a leader of the Serbian minority party and a staunchly pro-Kremlin Serbian journalist and a member of parliament from Vučić’s party, indicating attempts to interfere in the Macedonian turmoil.

According to Bechev, Russia’s principal interest in former Yugoslavia in general and in Macedonia specifically is to counterbalance the West.

“Moscow lacks a positive agenda but pursues opportunities to thwart its adversaries. The Kremlin is reluctant to expend scarce financial resources on the region, much less commit troops in order to claim a stake in Balkan security affairs. Meddling in local conflicts, through diplomatic channels or direct involvement in domestic politics, is, therefore, the strategy of choice. The ultimate objective is preventing the consolidation of the Western-backed order by freezing the status quo in the region”.

Why doesn’t that suit Moscow? Bechev underlines that unresolved disputes in the Balkans draw the attention of policymakers on both sides of the Atlantic away from Russia’s “near abroad” in the post-Soviet space.

Risks to Macedonia and the Balkans

Risks to Macedonia and the entire region are huge and the scenarios are dangerous. This position is doubtlessly shared by the four analysts.

Publicly pressured, unable to gather necessary 2/3 of votes in the parliament to make the required constitutional changes in line with the implementation of the Prespa agreement, Zaev calls new elections, Bandovic foresees.

“His SDSM wins the elections but precious time was lost in the process. Meanwhile, the Greek prime minister and Syriza pressed by their own electoral schedule, fail to ratify the Agreement in the Greek parliament. This scenario presents a huge blowback for the Euro-Atlantic future of Macedonia.”

Professor Nenad Markovic is one of the authors of the analysis

Markovic’s and Damjanovic’s opinions are in the same line, and they point out to the danger of conflicts and interethnic tensions:

“A failed referendum, combined with the possible progress of the idea of a territorial exchange between Serbia and Kosovo, might lead to a clear and present danger of interethnic zero-sum game, where more radical politicians in the Albanian campus might seek “compensation” for the blocked path to NATO and the EU. This could directly endanger the political stability of the country and put in danger interethnic relations, opening the possibilities for intensified political action by not just actors that oppose Macedonia’s EU and NATO integration, as well as drawing Macedonia into regional conflicts that it does not wish to be a part of”.

As Bechev puts it, the worst-case scenarios “would mean, in effect, a return to the pre-2017 status quo.

New governments led by New Democracy and VMRO-DPMNE can come into the office in Athens and Skopje. To make matters worse, the new cabinet in Greece may bow down to populist pressure and fall back on the maximalist position from the 1990s, insisting that no name containing the name “Macedonia” would be acceptable. There would be no scope compromise. However, Russia’s overtures to Macedonia would be sure to stoke interethnic tensions in the countries as well as beyond its borders.”

In his analysis, he gives several recommendations on how to avoid dark scenarios:

The West should engage with VMRO-DPMNE as well, along the way, following the example of Chancellor Angela Merkel; the bilateral dispute between Skopje and Athens needs to be converted, into a multilateral issue within the EU; NATO and the EU should invest into regional schemes for combating active measures, cyber warfare, fake news, and disinformation originating from Russia; The European Commission and EU member states should support independent investigative journalists, academics and think tanks researching the issue of foreign meddling in both Macedonia and Greece as well as in the region.

This article summarizes the analyses of Dimitar Bechev, Adjunct Professor of European Studies and International Relations at the University of Sofia where he teaches, Igor Bandovic from the Belgrade think-tank Regional Academy for Democracy and Nenad Markovic and Ivan Damjanovski professors at the Faculty of Law in Skopje.

Their analyses are part of the joint project for Support of Macedonia for Integration in the European Union and NATO of the Foundation Open Society – Macedonia.

The analyses can be found at:

Референдумот во фокус: крајот на патот за пристапување на Македонија во ЕУ и во НАТО или само крајот на патот?

Договорот за македонското име и по него: геополитичка перспектива

Патот на Македонија кон ЕУ и НАТО и регионалните импликации

Source: Deutsche welle

—————————————————

18 October 2018